Original 1987 (Reprint September 2022)

By Karl-Heinz Boska

Introduction

After The Defense of the Vienna Bridgehead article was published in the 1986 Armor* professional journal, several veterans from the Panzer Regiment Das Reich met to discuss the obvious impostor and false claims in the article. They selected Karl-Heinz Boska to write a rebuttal about what actually happened at the bridgehead between 11-14 April 1945. It was published in a German military history journal, whose name I have long since forgotten, in the late 1980s. Below is a translation from the original German. It never gained any traction in the United States or within the U.S. Army armor community.

Fritz Langanke sent a copy to the editor of Armor, who forwarded another copy to my father, “Arno Giesen.” My father never addressed the article, choosing instead to discredit Langanke through personal attacks. He did however use information from Boska’s article to further embellish his own stolen valor tales.

*Armor magazine is the journal of the U.S. Army Armor and Cavalry branch, read and respected by tens of thousands of military professionals since its founding by U.S. Cavalry officers in 1888, when it was originally title The Cavalry Journal. Armor has been a source of inspiration, fresh ideas, and historical information especially for junior officers and non-commissioned officers who form the backbone of the armored corps. The Giesen article influenced and inspired a generation of these up-and-coming leaders, who went on to fight and win the ground war during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Few of them knew the false background of the story.

A table of comparative ranks is at the end of this article and also short bios of the veterans involved in authoring Boska’s article.

The Article

Foreword

In January/February 1986, an article about the defense of the Vienna bridgehead during the final battles of 1945 appeared in the American military periodical “Armor,” a magazine about armored warfare. This article requires rectification. Former Hauptsturmfȕhrer Boska and our comrades Barkmann and Langanke have read the article in question.

All three are recipients of the Knight’s Cross and former members of the 2nd SS Panzer Regiment of the Division “Das Reich.”

The informant for the US “Armor” magazine, by the name of Giesen, was said to be a member of the Panzer Regiment “Das Reich.” He was neither in the division, nor a recipient of the Knight’s Cross. Thus, he never existed.

The article is largely untrue, but contains facts that indicate the magazine’s informant experienced some of what occurred. The personal experiences inserted into the article do not prove he was a front-line soldier of the Waffen-SS.

– The Editors

Boska’s Account

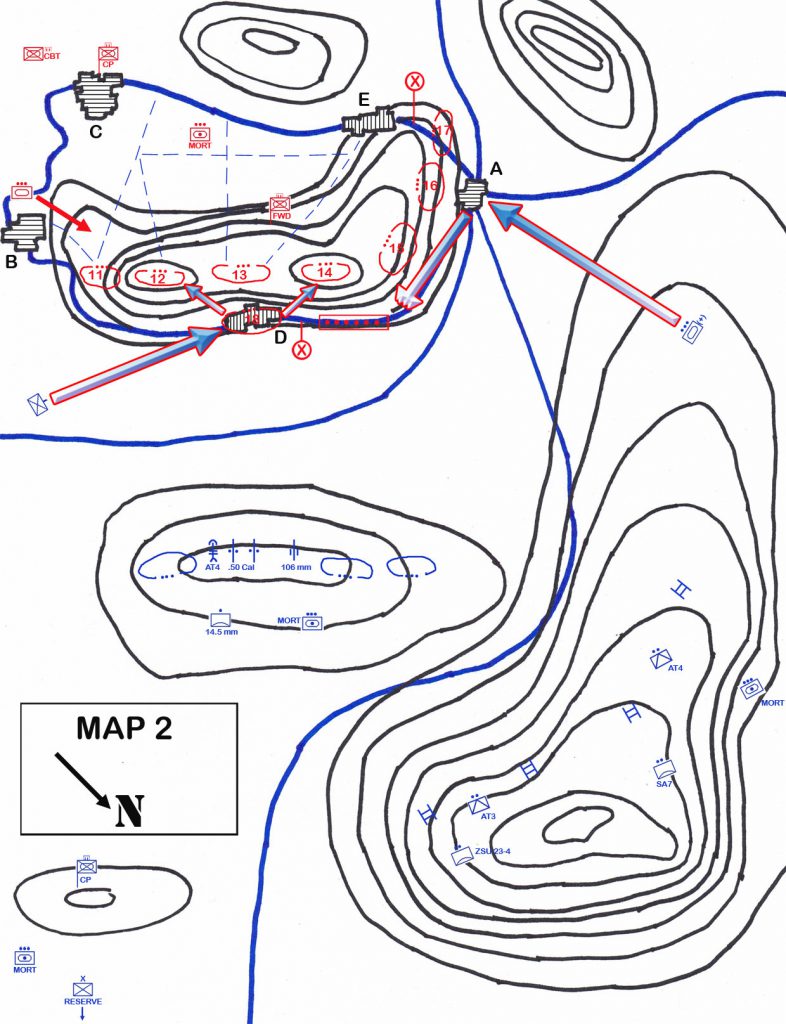

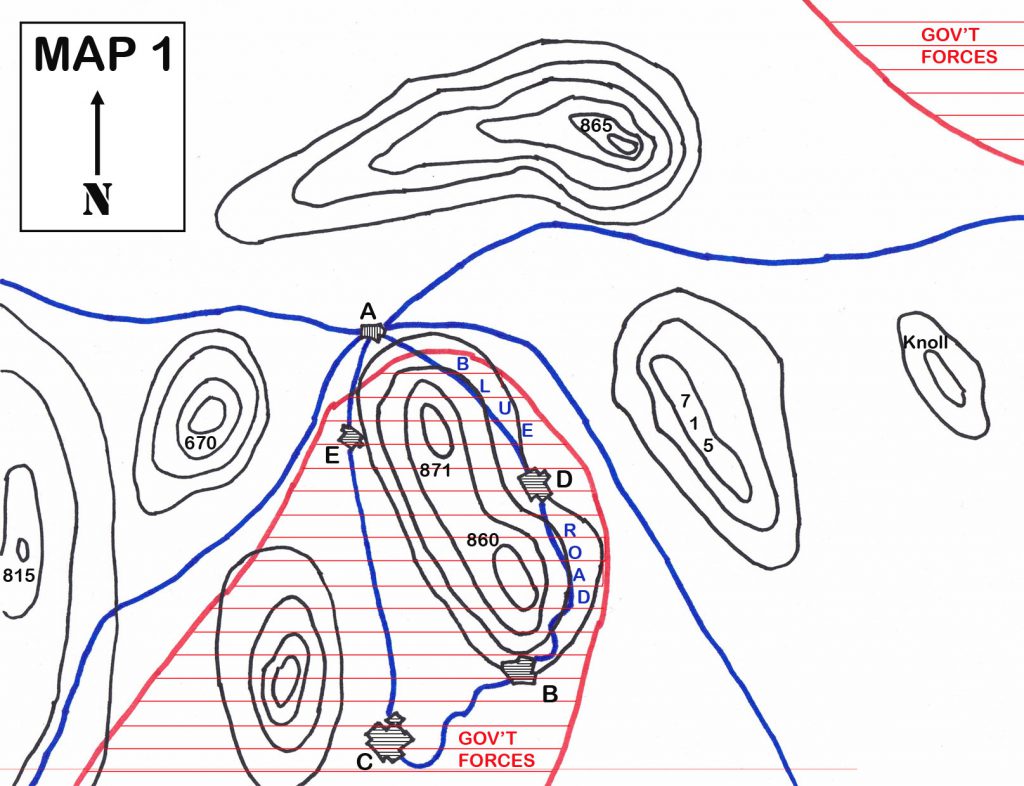

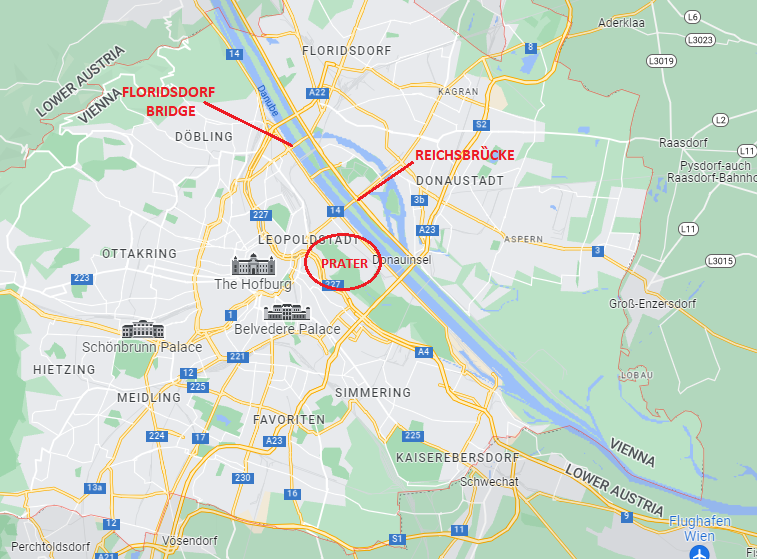

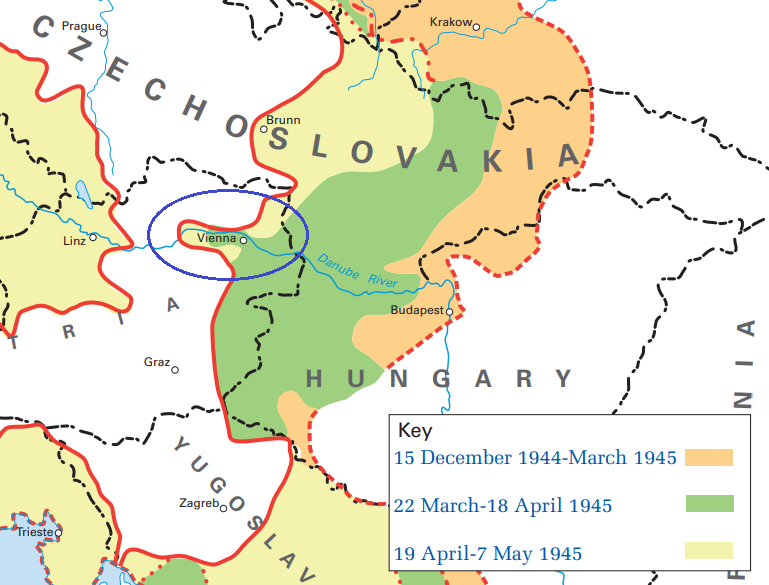

After almost all of the city had been given up, the final battle for Vienna took place in a bridgehead which stretched west along the Danube Canal to the Vienna Prater. While units from the Waffen SS defended the western portion of the bridgehead, it was predominantly a grenadier regiment from the 4th Panzer division that fought in the Vienna Prater [amusement park]. Since this division had no tanks available in the area of operations, the 6th Company of the Panzer Regiment “Das Reich,” consisting of eight tanks (Jagdpanther, Panther and Panzer IV), was attached under my command to this grenadier regiment from 11-12 April 1945.

The bridges to the north were the Reich Bridge (Reichsbrȕcke) and the Floridsdorf Bridge. Heavy fighting took place in the vicinity of the Vienna Prater and 84th Plaza. The tanks of the 6th Company were able to knock out several enemy tanks, but also lost several of their own tanks. The positions in the Prater were very difficult to hold during 12th of April and the Russians were advancing towards the Reich Bridge north of the Danube. The 4th Panzer Division therefore evacuated this portion of the Vienna bridgehead on the night of 12-13 April. The 6th Company’s tanks left the bridgehead at dawn on 13 April. For unknown reasons, the Reich Bridge was not blown up.

The situation north of the Danube had also become untenable for the 4th Panzer Division. I received an order from the division commander to return to my division in the Floridsdorf area. I moved my seven tanks through the suburban roads north of the Danube towards Floridsdorf. There, I found other units from my regiment, including the regimental staff. Individual tanks from the regiment, including tanks from the 6th Company, were sent to hot spots in the Vienna area by the regimental commander after they had undergone repairs at the maintenance company. As a result of this, the 6th Company lost a tank and its entire crew in a manner which is still unclear today. It was probably knocked out by partisans armed with a panzerfaust. The commander of this tank was Oberscharfȕhrer Hans Thaler, who was the first tank driver in the German Wehrmacht to receive the Knight’s Cross in Russia, in the Summer of 1943.

Knight’s Cross recipient Oberscharfȕhrer Ernst Barkmann, then with the panzer regiment’s 4th Company, also had his tank knocked out in the congested bridgehead at the Floridsdorf Bridge during the withdrawal of the front along the Danube Canal. He escaped with his life however.

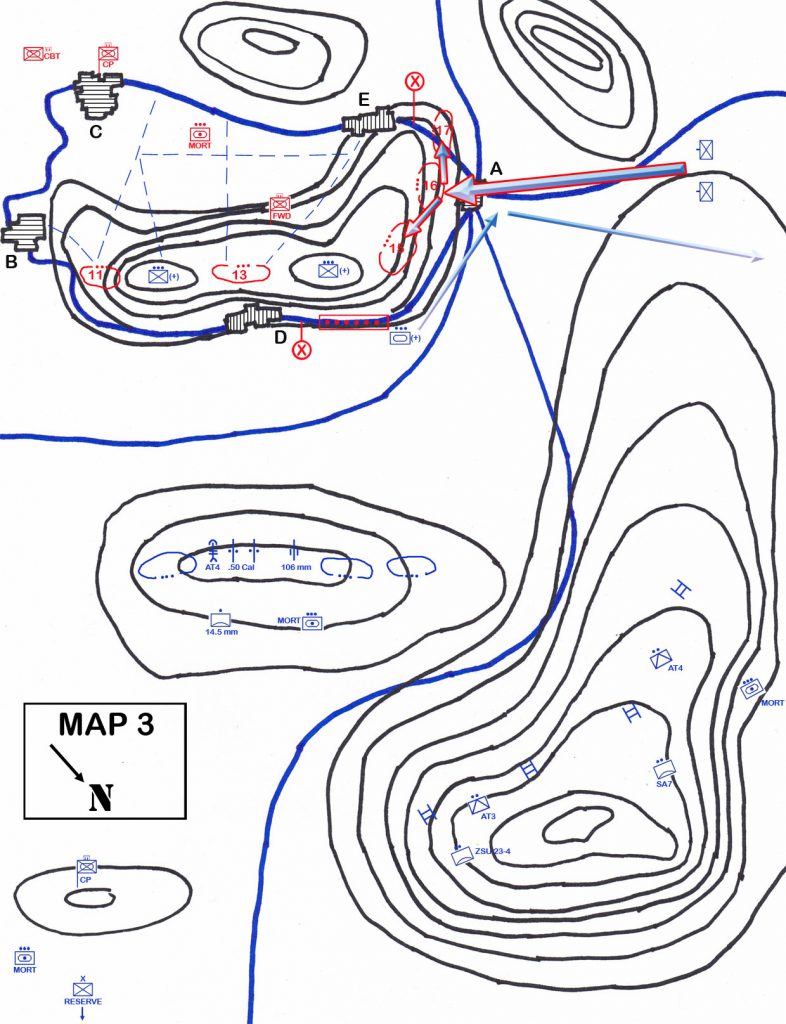

The evacuation of the units in the Prater area across the undamaged Reich Bridge had left a wide-open flank to the east. There were still two tanks from the 6th Company in the small bridgehead on 13 April. Due to their exposed positions, they were only able to take part in a portion of the fighting. These two tanks were a Panzer IV, under Oberscharfȕhrer Glazer, and a Panther, under Oberscharfȕhrer Schiner. Upon reporting to the regimental commander, I occupied positions on the northern bank of the Danube, west of the Floridsdorf Bridge. Two Panthers from the 2nd Company, under Untersturmfȕhrer Wahlmann, were also occupying fighting positions there. These tanks were attached to the 6th Company.

The regimental commander received an order from the division commander to send several more tanks across the bridge to reinforce the bridgehead until it could be evacuated on the subsequent evening. The division commander, Standartenfȕhrer Lehmann, had been wounded and was under the bridge. The narrow, heavily damaged bridge allowed for only very slow driving, and enemy observation from all sides made the destruction of our own tanks certain. My objections to this impossible mission went unheeded. Since the Panzer IVs and Jagdpanthers (Sturmgeschȕtz with an extra-long gun) were unsuitable for this mission, the company’s Panthers were the only option.

Due to the difficulty of the task, I assumed the mission myself. Since my command tank was a Jagdpanther, I took over Untersturmfȕhrer Wahlmann’s Panther and crew. Two more Panthers came along. I went forward to the bridge with the other two tank commanders, taking along Oberscharfȕhrer Barkmann (who had made many observations while crossing the bridge himself), to reconnoiter the specifics. There was virtually no movement in the area. Everyone was under cover because Russians placed artillery fire everywhere from their positions on the Vienna side. It was agreed that the three Panthers would cross the bridge with wide gaps between them.

As the first tank reached the center of the bridge, where there was a large hole, the second vehicle would begin crossing. The third vehicle would do the same when the second reached the middle. If the first tank were knocked out upon entering the bridge (the entrance was under enemy observation from numerous streets), the other two tanks would turn back. I rode in the first vehicle. As I passed the hole in the middle of the bridge, the second tank under Unterscharfȕhrer Ludwig van Hecke moved out. I now drove at a faster tempo onto the bridgehead. As expected, I came under heavy anti-tank and tank fire. A hit on the driver’s side front slope set the tank on fire. Both the driver and radio operator were killed, and the turret crew bailed out. I made an unlucky landing on a high curb, shattering my right heel. The gunner and loader remained unhurt.

The tank burned for several more hours. The second tank with Ludwig van Hecke drove back across the first half of the bridge as agreed upon, under heavy artillery fire. The third vehicle did not even move out. After managing to reach cover with my two men, I reported to the division commander under the bridge and described the failed mission. I successfully withdrew back across the bridge on foot with both my men that night and returned to my company. The bridgehead was evacuated that night, including both tanks still there. During the night of 13-14 April and the next day, all troops were evacuated west, under the most difficult conditions, from the northern bank and suburbs of Vienna. Along the Danube, the Russians could observe everything from the southern side. There was more enemy activity in the wooded high ground farther north as Russian forces infiltrated. The withdrawal was generally successful, as was the establishment of a new front line.

Equivalent Ranks

| Waffen SS Rank | Equivalent U.S. Army Rank |

| Standartenfȕhrer | Colonel |

| Hauptsturmfȕhrer | Captain |

| Untersturmfȕhrer | 2nd Lieutenant |

| Oberscharfȕhrer | Sergeant First Class |

| Unterscharfȕhrer | Sergeant |

Afterword

The three Waffen SS veterans behind this article were all very credible and verifiable members of the panzer regiment of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich. All three were verifiably in the area of the Vienna bridgehead during the time Arno Giesen claimed to have conducted his exploits. All three were of one accord that Boska’s version, not Giesen’s, is what actually occurred. All three are easily verified historical figures, unlike Giesen. As such, Boska’s account should be given much greater credibility. Short wartime biographies of the three Waffen SS soldiers are below.

Karl-Heinz Boska

Volunteered for the Waffen SS after the Polish campaign and served with the SS-VT (later Das Reich) reconnaissance battalion as an enlisted soldier during the Battle of France. He then served with the division’s motorcycle battalion during the invasion of the Balkans. He was selected for officer training and sent to the SS-Junkerschule, graduating in April 1942 as an Untersturmführer (2nd Lieutenant). He was assigned to the newly formed panzer regiment of the Division Das Reich as a platoon leader in the headquarters company. He was given command of panzer regiment’s 6th Company in October 1943. In November 1943 he led a ferocious counterattack against advancing Russian troops near Bolschaja Grab, a 2-hour battle destroying 12 Russian anti-tank guns, 2 field guns and killing 380 enemy soldiers. He was awarded the Knights Cross for this action. Boska was promoted to Obersturmführer (1st Lieutenant) in December 1943 and served in various division staff positions until returning to the 6th Company in September 1944. He was promoted to Hauptsturmführer (Captain) sometime during this period.

Fritz Langanke

Volunteered for the Waffen SS as a private before the war in 1937, rising up through the ranks to Obersturmführer (1st Lieutenant) by the end of the war. He served with the Germania regiment, first with the 10th Company and then the reconnaissance platoon, rising to the position of vehicle commander. He was awarded both Iron Crosses between 1940-41. He transferred to the panzer battalion in 1942, serving as a panzer commander in the reconnaissance platoon there. When the Division Das Reich reformed in 1943, Langanke served as liaison officer with the division’s panzer regiment until the Normandy invasion. In this capacity, he took it upon himself to organize and lead a group of hundreds of soldiers from various units, their vehicles and several tanks to escape from the Falaise Pocket. For this, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross. He took command of the 2nd Company of the division’s panzer regiment in December 1944 and remained at this post until the end of the war.

Ernst Barkmann

Enlisted in the Waffen SS as private before the war and was assigned to the Germania regiment, like Fritz Langanke. He fought in the invasions of Poland, France and Russia as a machine gunner. He was seriously wounded in July 1941 and was posted as an instructor training European SS volunteers. He transferred to the Waffen SS panzer arm in the winter of 1942, returning to Das Reich as a tank gunner. He was promoted to Unterscharführer (Sergeant) and given command of a tank just before the 3rd Battle of Kharkov in February 1943. Barkmann fought in Operation Citadel and remained on the Eastern Front until January 1944, when the division was transferred to France as reserve for the expected Allied invasion. During his time on the Eastern Front, he was awarded both Iron Crosses, Wound Badge in Silver and Infantry Assault Badge. He received the Knight’s Cross for actions near St. Lo shortly after the Normandy invasion and escaped from the Falaise Pocket afterwards, fighting many desperate rearguard actions all the way back to the German frontier. Barman was promoted to Oberscharführer (Sergeant First Class) and took part in the Ardennes Offensive, being seriously wounded on December 25, 1944. He saw final combat in Austria in March/April 1945, including Vienna. He surrendered to the British and became a prisoner of war.